Florida’s official state mammal ranks among the world’s most at risk of dying out.

Panthers have succumbed to disease, inbreeding, mercury poisoning and this year alone 21 have been listed by state authorities as road kills. Threats continue for the few hundred surviving animals, also called a puma, with suburbia invading their remaining Everglades refuge and rising sea levels expected to take more.

Panthers must expand their turf north, said conservation photographer Carlton Ward Jr. But the gap between Orlando and Tampa is a death row of traffic and development along six-lane Interstate 4.

Their best chance is to migrate from the Everglades, cross the expanse of wildlands that links South and Central Florida and includes DeLuca Preserve near Yeehaw Junction, and slip into wetlands and forests east of Orlando.

“I believe that is where we have the most to gain and the most to lose,” Ward said. “If there are going to be pumas in Georgia or the Appalachians again, they’ve got to get through that landscape.”

Ward’s vision may sound as grandiose as when Fred DeLuca and Anthony Pugliese sought to turn a 27,000-acre tract into the city of Destiny. Their success would have dynamited conservation prospects for wilderness and ranchlands between South and Central Florida.

But Destiny failed. DeLuca’s widow gave the land as DeLuca Preserve to the University of Florida. Ward turned his dream into action.

Ecological toughness

Career environmentalist Richard Hilsenbeck was driving along Florida’s interior spine of sand dunes a decade ago when he joined a conference call with Ward and others.

The callers would back an audacious strategy to rally political and popular support for connecting the state’s habitats, its panthers and many other wildlife that would atrophy if left marooned.

Connecting parks, forests and other conservation areas with new corridors of protected lands would bring greater ecological toughness in the face of population growth, climate change and economic booms and busts.

“In a high-growth state, a lot of people didn’t think you could do this,” said UF conservation scientist Tom Hoctor, who was on that call.

Hoctor works in data, policy and planning. He earned his PhD under UF’s Larry Harris, who was the major professor of Reed Noss, later a University of Central Florida professor. The three forged academic underpinnings for connecting the state’s environmental prizes.

With a doctorate in botany, Hilsenbeck was a project director at The Nature Conservancy who evaluated the health of lands, spent time with owners and arranged acquisition deals. He helped forge the underpinnings of environmental advocacy for connecting landscapes.

Florida’s nature has been ailing since its old-growth forests were cut down a century ago. Not all is lost. The past half-century has seen scores of victories in the 800 miles between Key West and Pensacola.

Among them, Picayune Strand State Forest, a cypress wonderland near Naples, rose from herculean assembly of land-scam lots. Allen David Broussard Catfish Creek Preserve State Park in Polk County saved ancient, exquisite, desert-like terrain. Wekiwa Springs State Park, in Orlando’s shadow, supports a high density of bears. The Panhandle’s Topsail Hill Preserve State Park features towering beach dunes and virgin forest.

By the end of the 1990s, the formal framework for connecting those jewels and many others, known as the Florida Ecological Greenways Network, quietly had been written into law.

“It was behind the scenes,” said Hoctor, who directs the UF Center for Landscape and Conservation Planning in Gainesville. “Most people didn’t know it even existed.”

Also problematic was the flatlining of conservation progress with the Great Recession and then-Gov. Rick Scott defunding environmental protections.

Great story

“No one, to my knowledge, had uttered ‘Florida Wildlife Corridor’ until Carlton threw that out during the call,” Hilsenbeck said.

An environmental epoch, baptized in a conference call, got a name.

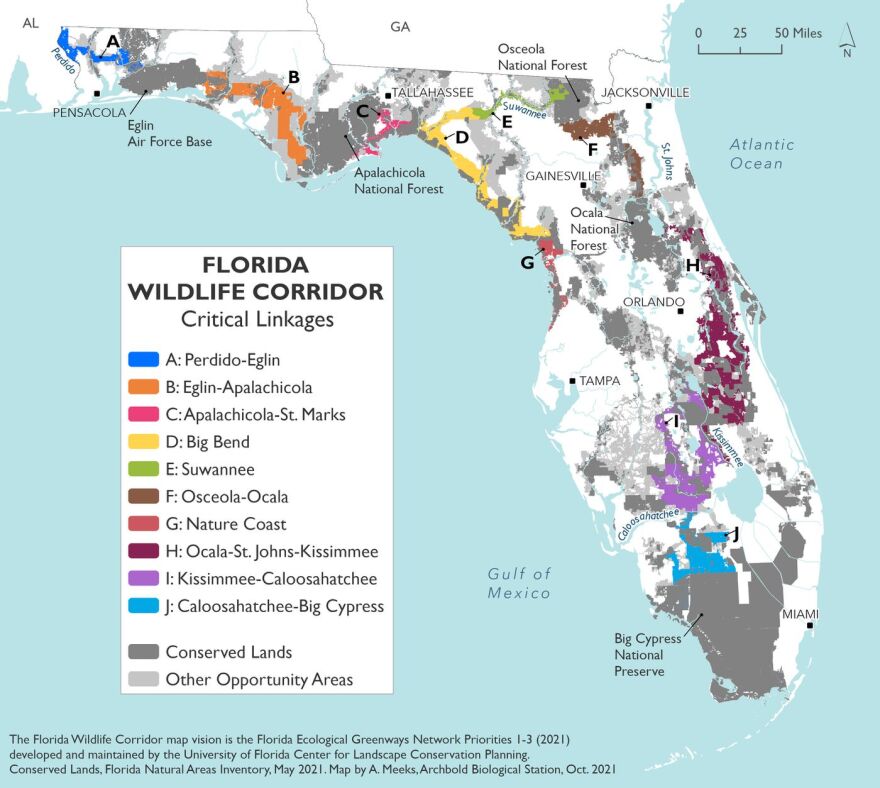

The vision for the Florida Wildlife Corridor concept starts with 10 million acres of preserved lands across Florida and aims to link them by acquiring another 8 million acres not yet protected. The result would be continuous corridors for wildlife throughout the state.

Ward had his work cut out. He and cohorts launched expeditions, crisscrossing habitats, shouldering backpacks, paddling through storms, tent camping and inviting VIPs to trek along.

“That’s what really started to get people fired up about it to say ‘yes, it’s doable’ and that, ‘gosh, we really need more money,’” Hilsenbeck said.

One such person was Arnie Bellini, who in 2019 sold the Tampa Bay tech firm he founded, ConnectWise, for $1.5 billion. In giving back to his community, he pivoted to underwriting creation of high-paying tech jobs, but also seeking to balance economic growth with environmental protection.

“What I learned in business is you need a great story,” Bellini said. That came along scripted as the Florida Wildlife Corridor.

“We are in a lot of ears trying to make this into a big movement,” Bellini said. His foundation has backed wildlife research, purchases of sophisticated camera gear, applications of artificial intelligence, acquisition of environmental lands and the hiring of two prominent lobbying firms, Ballard Partners and Southern Group, to persuade legislators early this year to protect wildlife corridors.

“All told, we’ve put $30 million into the corridor effort,” Bellini said, describing himself as “incredibly optimistic about being able to save the last intact wildlife corridor east of the Mississippi River.”

Bellini acknowledges he arrived at a ripe time. The Florida Wildlife Corridor has become supported by a coalition of the state’s major and many environmental actors. The concept has been widely promoted as the glue for joining and protecting the fruits of their previous labors, the parks, preserves and places of healthy nature across Florida. Now, suddenly, it’s solidifying.

Lawmakers this year allocated $400 million for acquisition of environmental lands.

“I believe in pendulum swings,” said Hoctor, who views his role as professor and scientist, advising advocates and lawmakers.

From 1980 until the Great Recession, Florida was a leader in balancing growth with development rules and land acquisition, Hoctor said.

This year, Florida’s development machine kicked into a higher gear, renewing fears the state is blighting itself with pavement and rooftops.

“Legislators are not blind to that,” Hoctor said. “I think there is a new attitude in the Legislature about where we are at and where we are headed.”

In September, the Florida Cabinet authorized $15 million to buy development rights for 6,665 acres of Wedgworth Farms and $14.5 million for the outright purchase of 4,381 acres of Corrigan Ranch. Both are close neighbors of DeLuca Preserve at Yeehaw Junction in south Osceola County.

Corrigan Ranch acres delivered a bonus analogous to if you build it, they will come. Proponents of buying the property knew if you buy it, they will be there.

“They” are endangered Florida grasshopper sparrows.

Secret sauce

A few years ago, conservationist Julie Morris wrote the proposal to state and federal authorities to acquire Corrigan Ranch. In doing so, she hired a consultant for an ecological evaluation of the property.

“He suspected he heard Florida grasshopper sparrows,” Morris said. “So he went back out and did surveys and found a previously unknown population of the Florida grasshopper sparrow, which is a really big deal.”

As with ranchland at DeLuca Preserve, Corrigan Ranch has a secret sauce for finicky sparrows. They had been regarded as averse to pasture, intolerant of cattle and able to survive only in natural prairie.

The finding of sparrows on those two ranches, said Audubon Florida’s Paul Gray, “is priceless” for prospects that the small, brown bird will claw its way back from the brink of extinction.

“I had a biologist ask me what the heck I did to create that and I said all we did was manage for cattle,” said Tad Corrigan.

“We never overgrazed anything. We did some chopping. We mowed. We did controlled burning,” Corrigan said. “It’s created really good habitat for some of the species that are not readily found in the state anymore.”

A champion

Many of Florida’s parks, preserves and forests are globally significant.

South Florida’s Everglades National Park was created in the 1930s with 1.5 million acres. Its neighbor, Big Cypress National Preserve of 720,000 acres, came to be in 1974.

In the Panhandle west of Tallahassee, the state in 1994 purchased 202,000 acres that now comprise Tate’s Hell State Forest, which borders the 630,000-acre Apalachicola National Forest.

Near Jacksonville, the state in 2001 acquired 38,000 acres, now John M. Bethea State Forest, to link the Osceola National Forest of 200,000 acres with Georgia’s Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge of 400,000 acres.

The Florida Wildlife Corridor proposes to link all of those, plus Picayune Strand, Catfish Creek, Wekiwa Springs, Topsail Hill and many other treasured lands in between.

To do that, in Ward’s view, corridor protections absolutely must extend from home plate deep in the Everglades to first base east of Orlando.

That corridor embraces headwaters of the Kissimmee River and of the St. Johns River.

Also within that expanse is an alphabet soup of different owners and different missions — ecosystem and wildlife research, national defense, water conservation, hunting, habitat protection, park space, cattle ranching and the outdoor classroom at DeLuca Preserve — all aimed at conservation.

There is no celebratory name for that wild landscape between Central and South Florida.

There is, of course, a champion.

The mascot of the Florida Wildlife Corridor is the black bear, which has endured and even thrived in multiple groups across the state.

But Ward champions the panther as the species whose survival hinges critically on corridor success. He already is hunting for them in DeLuca Preserve, placing remote cameras there.

It’s a painstaking way to take pictures, resulting often in nothing, some near-misses and rarely a stunner of a portrait with the right lighting, position and ferocity.

“You’re basically building a commercial photo studio that has to be waterproof and endure the elements and trigger in a fraction of a second when an animal happens to walk by,” Ward said.

Stellar scenes

He was reminded of wandering in DeLuca Preserve.

The place is so removed from the incandescent schmutz of cities that night rivals day for stellar scenery.

The Milky Way glows as a celestial comforter, the lip of the Big Dipper finds the North Star and forest silhouette provides staging.

Nights in the far-flung space are a theatrical shoutout to Florida’s original virtuoso, nature.

“It’s an awe-inspiring place to stand and look up and feel small and also feel a little sad that so few people in Florida get to see that,” Ward said.

“You are reminded that you are in a truly wild and vast place that is so fragile and so close to so much development.

“It snaps you out of your own world to realize how …”

Ward’s pause lasted a few long beats.

“How infinite everything is.”

Braided strands

If a place of destiny near Yeehaw Junction in south Osceola County doesn’t tug at infinite, then it must pull on a thick rope of braided strands twisting together for decades.

Of the many strands, Fred DeLuca co-founded Subway in the 1960s, becoming a billionaire and then aspiring at the height of the housing bubble and the eve of the Great Recession to turn 27,000 acres in south Osceola County into a city called Destiny.

His widow donated the acreage of the failed Destiny to the University of Florida as the renamed DeLuca Preserve, sparking hope for preservation of the surrounding landscape and for wildlife corridors throughout Florida.

Informed by ecosystem science, unflagging advocacy and policy forged over decades, lawmakers this year invested heavily in environmental lands.

Recently, the state approved purchases of lands for conservation, including within the expanse of wildlands that includes DeLuca Preserve.

That surviving frontier between Central and South Florida is where ranchers, panthers, sparrows, wiregrass, longleaf pines and Florida’s unique prairies may thrive for a long time.

Or, as long as the stars shine favorably above where natural Florida’s future is turning.

Kevin Spear has reported for nearly 30 years on Florida protection of environmental lands. He tent camped, explored and joined researchers at DeLuca Preserve. kspear@orlandosentinel.com

This story was produced in partnership with the Florida Climate Reporting Network, a multi-newsroom initiative formed to cover the impacts of climate change in the state.

Copyright 2021 WUSF Public Media - WUSF 89.7. To see more, visit WUSF Public Media - WUSF 89.7. 9(MDA4MzM1MjM1MDEzMTg5NTk0MzNmOTQ5MA004))